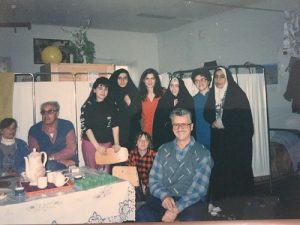

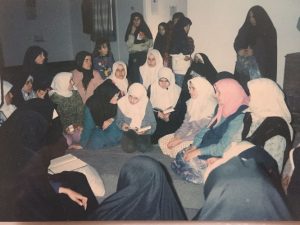

HAMI started out as a volunteer and independent organization during the Balkan crisis in 1992 to provide help for vulnerable women and children suffering from persecution and abuse in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Remembering the Bosnian Genocide

his week in Srebrenica, a once little-known Bosnian town now synonymous with genocide, volunteers poured strong Bosnian coffee into more than 8,000 small porcelain cups called fildžani. They will remain untouched.

The cups symbolize the more than 8,000 innocent victims of the Srebrenica genocide, men and boys who were brutally murdered a quarter-century ago by Belgrade-backed Bosnian Serb forces who overran the town, a demilitarized safe zone designated by the United Nations. More than 25,000 women, children, and elderly people were forcibly deported; many suffered rape, physical or psychological torture, or other crimes. This horrific act served as a wake-up call to the United States and other countries, and led in no small part to the signing of the Dayton

Peace Accords in November 1995.

Tomorrow, the world will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide. Eight funerals will take place for victims whose remains were identified in recently unearthed mass graves. And more than 8,000 coffees — the basic currency of social interaction in Bosnia-Herzegovina — will remain undrunk. The cups form an art installation created by Bosnian Muslim artist Aida Šehović entitled “ŠTO TE NEMA,” which translates as “Why are you not here?”

For the friends and family of the victims, that question is a wrenching search for meaning in the senseless cruelty of war. For the international community, it is an urgent reminder that less than 50 years after we pledged “never again” when faced with Nazi atrocities in World War II, we stood by as genocide and crimes against humanity were committed once again in the heart of Europe — this time under the watchful eye of U.N. peacekeepers.

For a time, the stain of Srebrenica on the collective conscience of Western democracies translated into policy change and action. In 1999, NATO forces bombed military targets in Yugoslavia to force an end to ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. Ad hoc tribunals to try crimes committed in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Rwanda made way for the International Criminal Court. U.N. member states adopted the “Responsibility to Protect,” taking it upon themselves to individually and collectively prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.

Over time, though, our attention began to wane. New policy problems and paradigms arose, from the war on terror to great power competition; a global financial crisis to a global pandemic. Conversations about human rights and shared values were muffled or magnified based on whether the subject in question was classified as a friend or a foe. In many places, populism gave way to nationalism, while politicians and their proxies used social media to widen political, racial, ethnic, and religious divides. The lights began to flicker in the shining city on the hill.

In Syria, Bashar Assad has used chemical weapons against his own people in the civil war that has raged since 2011 and cost more than 400,000 lives. In 2016 and 2017, more than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims fled Myanmar in what the United Nations has called a textbook example of ethnic cleansing, and possibly genocide. More than a million Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other mostly-Muslim minorities endure forced labor and “reeducation” in camps in western China. Last year, as if to underscore George Santayana’s oft-quoted saying that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” the Nobel Committee bestowed its literature prize on Peter Handke, a notorious supporter of Slobodan Milošević and denier of the Srebrenica genocide.

Twenty-five years after Srebrenica, we are once again facing a wake-up call. It would be easy to press snooze, to wait until we have passed the peak of the pandemic, until our economies have recovered, until great power competition has become less acute. But if there is one thing I learned in almost 15 years in government, it is that there is never a “good time” to prioritize human rights.

I have little hope that the Trump administration will heed this call; it is more likely to continue using human rights as a club to batter its enemies abroad, while denying growing calls for justice at home. The American brand President Trump hands over to his successor, whether in four months or four years, will be badly tarnished. Yet our history shows we are capable of learning from and moving beyond our moral failings, if we allow our values to guide us. This is what the state of the world will demand from our next president; if there is ever any doubt, there are more than 8,000 coffee cups in Srebrenica to serve as a reminder.